There is a fearsome and surly troll who makes her lair on the front steps of our house. I’m not quite sure why, but her nemesis is the spritely and powerful FLASH who is always daring to disturb her slumber. FLASH is powerful because he can walk in lava, drop earthquake bombs, throw electricity and fire and also he has wind power. The troll can do none of those things, and can only occasionally muster the energy to employ her HULK SHIELD but usually that catches on fire and she either slinks back to her lair, or ends up dead on the grass somewhere.

But once, after a particularly spectacular lava/earthquake/HULK SHIELD battle, which left the troll powerless and still on the grass, FLASH brought her a flower, plucked from the lawn on the other side of the driveway – I mean lava pit.

Now, this wasn’t just any flower. No. This was the flower of love, FLASH explained. And the flower of love transforms the angry troll back into FLASH’s loving mother. They cuddle and rest for a bit, maybe play on the swing, and then go in for a snack.

Do you ever notice a lesson that you thought you had already learned revealing itself to you again, in a new way? I thought I knew that play is a language of children – one of “the hundred languages” central to the Reggio Emilia experience, articulated so beautifully in Loris Malaguzzi’s poem, “No Way. The Hundred is There”. This time at home with my children is bringing that lesson up, again and again, right up to my nose, waving a sign in front of me that says, “Play is his language!”

I’m learning to listen to that language again. I’m hearing it in a new way. From the same poem:

“A hundred, always a hundred

ways of listening…”

– Loris Malaguzzi, No Way. The Hundred is There.

Play as Therapy

I also thought I knew that play is therapeutic. When my son first brought me the flower of love, I thought, “whoa, now there’s a metaphor”. I lose my patience regularly – more regularly than I would like. Playing an ugly, angry troll feels better than actually transforming into one. It’s an outlet. And I melted when he brought me that flower. Having found that feeling in play, I’m finding it easier to access in real life.

We hold a lot of time and space in our Forest and Nature School Practitioners Course for adults to play. For many of us, that’s really hard to do. It’s often uncomfortable, especially at first. I myself actually rarely play during a course. I have a concept of myself as not really being that into play, or good at it. But in reflecting on this game I enjoy so much with my son, I’ve realized that I actually really love this kind of superhero fight play. I like wrestling. I also like building forts and digging in the dirt.

So…what? Why does playing as adults – as caregivers and educators – matter?

And, now what?

Finding curriculum in play

If you were an educator wondering (worrying?!) about how to meet curriculum while starting from outdoor play, how might you build on this game? My first instinct is to look to the language curriculum. The flower of love game is a form of story making. We could use it as a writing prompt, an invitation to create a comic, or an illustrated story book. Or an audio book. Or a podcast.

I did drop some bait for my son around writing down our game as a story. “Maybe tomorrow,” he said. “Or we could record it?” Not quite interested in that, either. I may try again another time.

So, I’ll think back to my Grade 1/2 teaching days, and imagine what I might do as a classroom teacher. Imaging possibilities and preparing to support those possibilities is the form planning takes for me as an educator striving to nurture emergent, child-led learning.

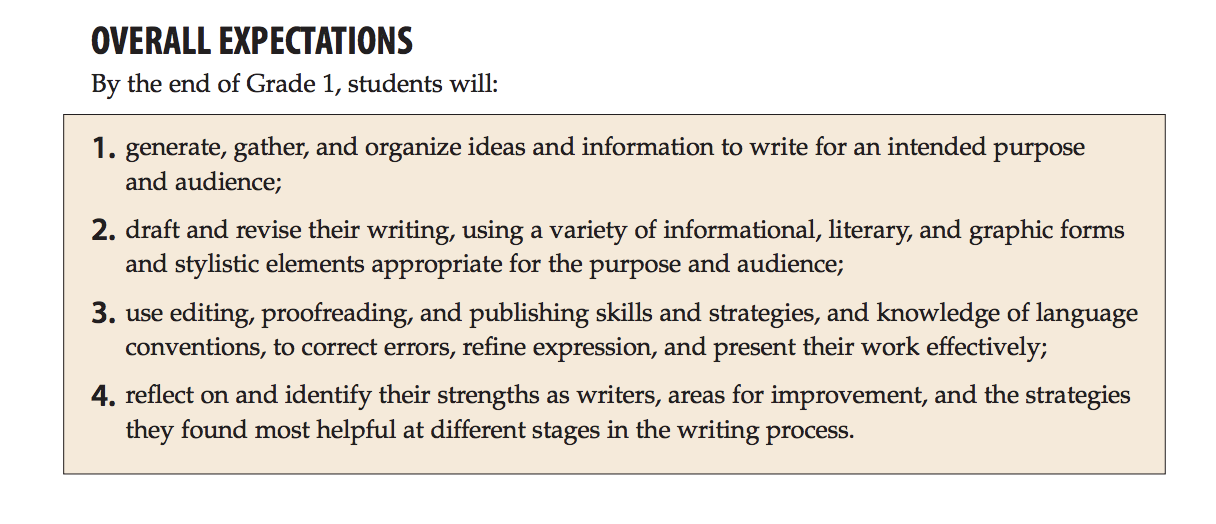

As I look through the Ontario Grade 1 Language Curriculum, I can picture students transforming their play into story, either individually, or in the groups they’ve shared the games with, or as a whole group. In choosing how to “storify” or document their play, they would be practicing the skills outlined in the writing expectations, and I as the educator would scaffold that process as needed.

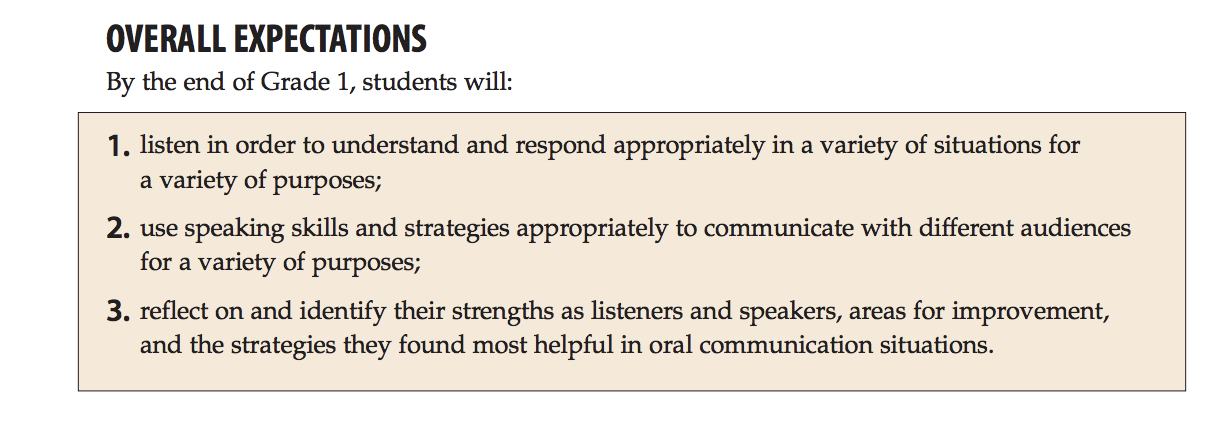

If they chose to make an audiobook or podcast, they could practice the skills outlined in the oral communication expectations (i.e. overall expectation 2, below) and by inviting and supporting students to listen to each other’s work, they could strengthen the reflection and metacognition skills described in the curriculum.

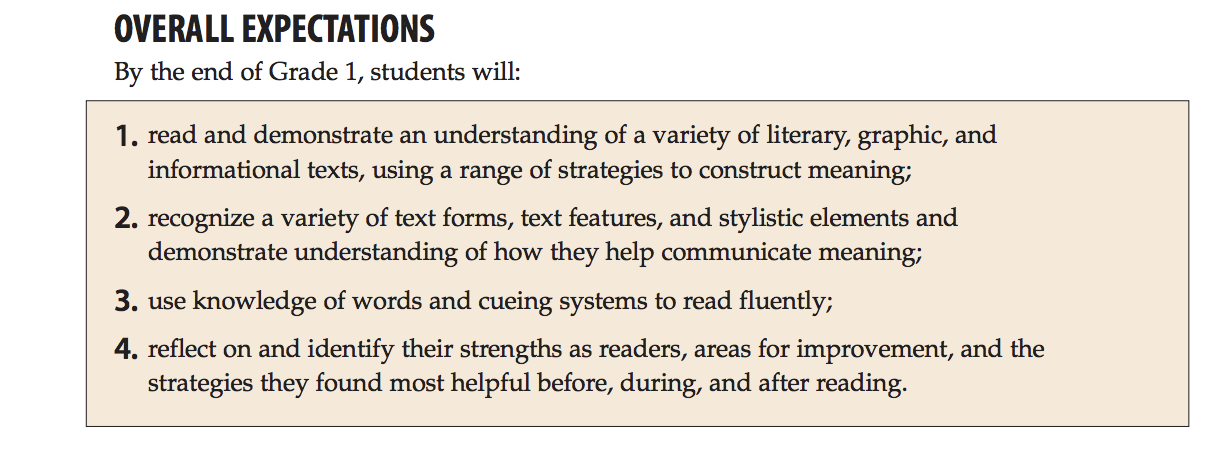

Similarly, by reading each other’s work – which may be more motivating to some readers than commercially published books – and especially if the children chose to create a variety of writing styles to convey their play (i.e. comics, story books, how to guides, etc.) – students would have opportunity to engage with the reading expectations outlined in the curriculum. I as the educator to support the children to discuss their work, thereby engaging with the reflection and metacognition skills outlined in the curriculum.

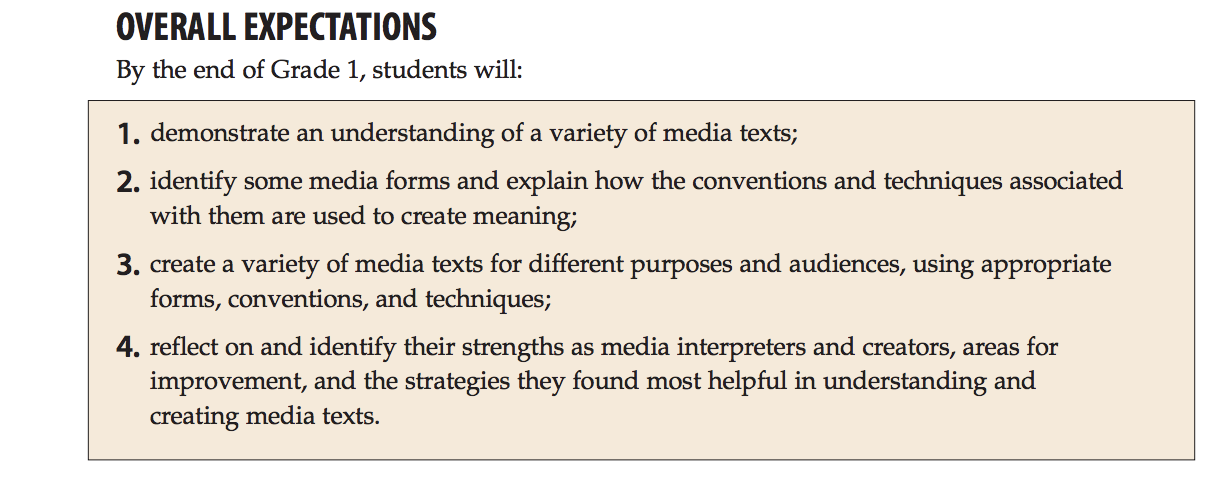

In the particular case of the flower of love game (or any fighting/superhero style games), I see many possible connections to the media literacy curriculum and opportunities to plant seeds of critical thinking around what kinds of tv shows or ad are geared towards which audiences (i.e. is this superhero show “for boys”? Why? Why not? What makes a “good guy” good? What makes a bad guy “bad”?)

In the particular case of the flower of love game (or any fighting/superhero style games), I see many possible connections to the media literacy curriculum and opportunities to plant seeds of critical thinking around what kinds of tv shows or ad are geared towards which audiences (i.e. is this superhero show “for boys”? Why? Why not? What makes a “good guy” good? What makes a bad guy “bad”?)

What other curriculum connection could you imagine growing from the Flower of Love? Let us know!